That sentence seems obvious enough that I would not need to write it. But there does seem to be a strain of thought out there that sees China’s economic system, with its high levels of state ownership and extensive planning, as basically the same thing as the mixed economies that Western Europe had in the immediate postwar decades, which featured more state ownership and planning than after the 1980s. In this view, China today confronts the Western economies not with a completely foreign economic system, but with an image from their own past, a reminder that they have drifted too far in a market fundamentalist direction. The most prominent proponent of this line is probably Thomas Piketty; his recent commentary on China includes this passage:

On the economic and financial level, the Chinese state has considerable assets, much greater than its debts, which gives it the means for an ambitious policy, both domestically and internationally, especially regarding investments in infrastructure and in the energy transition. The public authorities currently hold 30% of everything there is to own in China (10% of real estate, 50% of companies), which corresponds to a mixed economy structure that is in many ways comparable to that found in the West during the period of prosperity 1950-1980 (known in France as the ‘trente glorieuses’). Conversely, it is striking to note the extent to which the main Western states all find themselves in the early 2020s with almost zero or negative patrimonial positions.

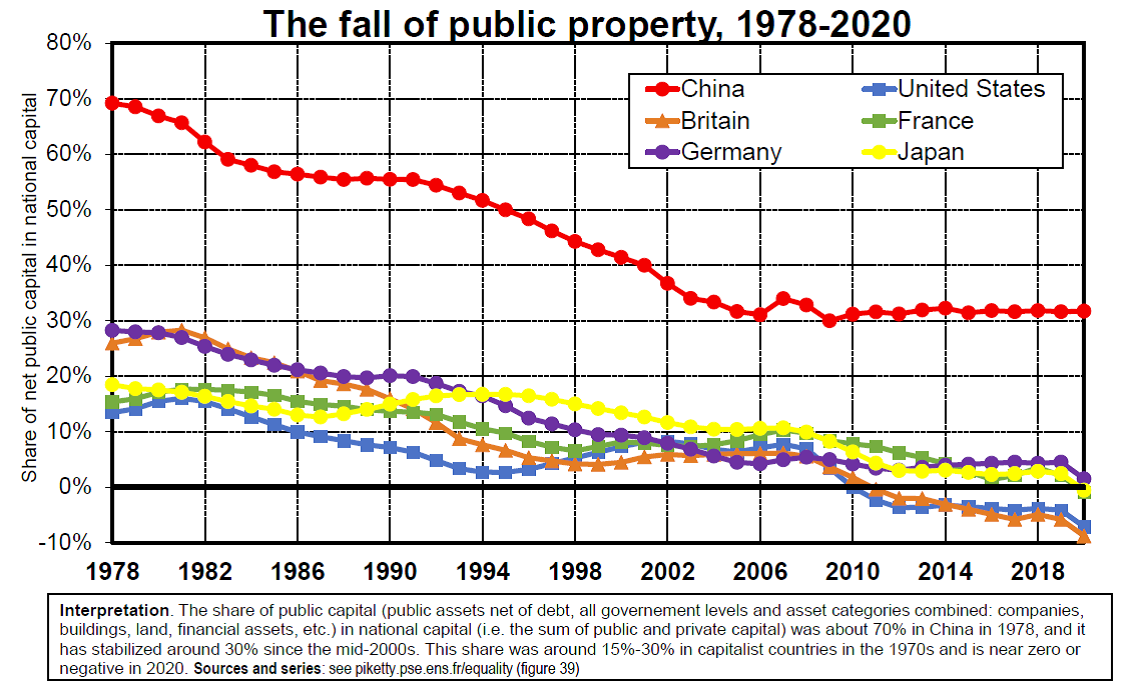

Piketty’s comparison is based on empirical data: the estimates he made, in a joint paper with Li Yang and Gabriel Zucman, of the extent of government ownership of assets in China. He finds that China’s recent level of 30% is similar to the 15-25% that prevailed in Western countries in the 1970s. So if you squint at his chart, the line for China today does get close to the lines for Britain and Germany in 1978.

The good thing about data is that they can challenge your intuitions. Still, the claim that an authoritarian state that spent decades under socialism has basically the same political-economic structure as that of the postwar European democracies is not the world’s most obviously plausible argument. And looking at different data indeed tells a different story.

When I’ve tried to grapple quantitatively with the question of the role of the state in China’s economy, I’ve focused on state-owned enterprises, whose large role is one of the most obviously distinctive features of China’s system. China’s own official data on state-owned enterprises imply that they have generated value-added equivalent to around 25-30% of GDP in recent years. (If you don’t believe my numbers, there is a World Bank paper that comes to basically the same conclusion using different methods). Conceptually, these figures represent the flows of income generated by the stock of assets counted by Piketty.

We can compare these numbers to historical figures for European and other economies thanks to an IMF research project from 1984 published as the the book Public Enterprises In Mixed Economies. According to these estimates, state-owned enterprises accounted for 12-13% of GDP in France in the 1960s, 10% of GDP in Germany in the 1970s, 7% of GDP of Italy in the 1970s, and 10% of GDP in the UK in the 1960s and 1970s. After the privatization wave of the 1980s, state-owned enterprises in the UK accounted for about 2-3% of GDP, according to the 1995 World Bank study Bureaucrats in Business (it did not have more recent estimates for continental Europe). In the US and Japan, state-owned enterprises have historically been about 1% of GDP.

The state-owned enterprise sector in China today, therefore, is actually two to three times larger relative to the economy than it ever was in continental European economies. And China’s state enterprise sector is 10-15 times larger than the now quite minimal state sectors in the English-speaking economies. Those are big differences! It seems clear that China’s socialist market economy is quantitatively and qualitatively different than the mixed economies of the postwar European social democracies, as indeed we should expect given their quite different political foundations. When these economies engage with China, they are not engaging with a version of their past selves but with a quite different kind of entity. I think these differences make China more interesting and worth understanding than if it were just retreading the past trajectory of Western Europe.

It is true that the European economies had sustained fast growth in the postwar decades, which invites comparison to the sustained fast growth of China in more recent decades. But in both cases I would point to the magic of catch-up growth and trade liberalization as the most obvious drivers (on this, see Brank Milanovic’s interesting comments on the misplaced nostalgia for Europe’s postwar years). Europe in 1945 and China in 1978 both had quite backward capital stocks that could be rapidly expanded and modernized, as well as relatively high levels of human capital that could be productively deployed once war and political turmoil were over. And in both cases increased participation in global trade, through the European Community/European Union or GATT/WTO, could further accelerate specialization and technological progress.